How dangerous does the United States government think El Salvador really is?

Depending on how you look at it, the government’s answer to that question is either nuanced or dangerously inconsistent.

In January, Secretary of State John Kerry announced that the US will be devoting particular attention to finding and processing refugees in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala to bring to the United States. But the administration is simultaneously continuing the nationwide raids it started in the first days of 2016 to find and deport families who had failed to get asylum and been ordered to leave the country.

In other words, at the same time that the US is promising to bring people out of Central America to the US, it’s fighting very hard to send some Central Americans back.

To advocates, immigration judges, and Central American diplomats, it’s a dangerous paradox. There appear to be serious concerns that the same people the US wants to save from danger in Central America are the ones it’s deporting.

“The administration continues to support refugee processing programs while ignoring those already in the United States,” says Jose Magana-Salgado of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. The problem, he says, is “the broader theme in the administration’s foreign policy: Individuals fleeing persecution and violence are ‘undocumented immigrants’ if they are from Central America and ‘refugees’ if they are from anywhere else.”

The government wants to provide a “safe, legal” path to the US — but it might take years

The US doesn’t set firm caps on refugees from particular countries — instead, it sets targets by region, based on where it’s allocating resources to process refugee applications to begin with.

In recent years, the government simply hasn’t put a lot of effort into taking refugees from Central America. Now it’s promising to change that. For those advocating for refugees, the best-case scenario is that in a few years, the US will be letting in as many refugees from Central America as it currently does from the Democratic Republic of Congo: a few thousand a year.

“I don’t think it’s going to be a massive protection mechanism,” says Wendy Young, the director of Kids In Need of Defense and a leading refugee advocate. “At least not initially.” And she cautions that “it’s going to take a while to set up.”

People fleeing imminent danger don’t have that kind of time. This is one of the biggest problems with refugee admissions.

Young and other advocates have expressed hope that the US and United Nations will figure out some way to protect the people being processed — maybe by bringing them to a third country while their applications go through. But that’s a big question mark.

International law requires countries not to send anyone back to a place they might be in mortal danger. And in some cases, when the US has been concerned enough about security in a given country to expand refugee operations there, it’s also been concerned enough to protect people living in the US from getting sent back to that country — by granting them something called temporary protected status (TPS).

That’s what Magana-Salgado’s group is arguing the administration should do now for Central Americans. Magana-Salgado points out that this is what happened with Syria: The US granted TPS to Syrians in the US in 2012, “to complement the United States’ broader efforts to admit Syrian refugees.” But he and other advocates allege that when Central Americans flee to the US without papers, the administration is more interested in treating them as unauthorized immigrants than as refugees.

The administration believes not everyone fleeing Central America is equally in danger

As far as the law is concerned, there’s no such thing as illegal immigration for asylum seekers: If you’re coming to the US to seek asylum, it doesn’t matter whether you have papers or not. But as far as the Obama administration is concerned, thousands of people coming to the US without papers is a bad look.

The administration paints this as a humanitarian concern. When Secretary Kerry announced that the government would expand refugee processing in Central America, he said he wanted to “offer [refugees] a safe and legal alternative to the dangerous journey that many are tempted to begin, making them at that instant easy prey for human smugglers who have no interest but their own profits.”

But it’s also a matter of enforcement. The government thinks simply coming from Central America doesn’t necessarily mean that someone is in mortal peril, and they want to be able to distinguish the legitimate refugees from everyone else. “While we recognize the serious underlying conditions that cause some people to flee their home countries,” a senior administration official told Vox, “we cannot allow our borders to be open to illegal migration.”

So some people — those who come to the US, seek asylum, and have their cases rejected — are getting sent home. Essentially, the US is saying that Central America is dangerous, but not for them.

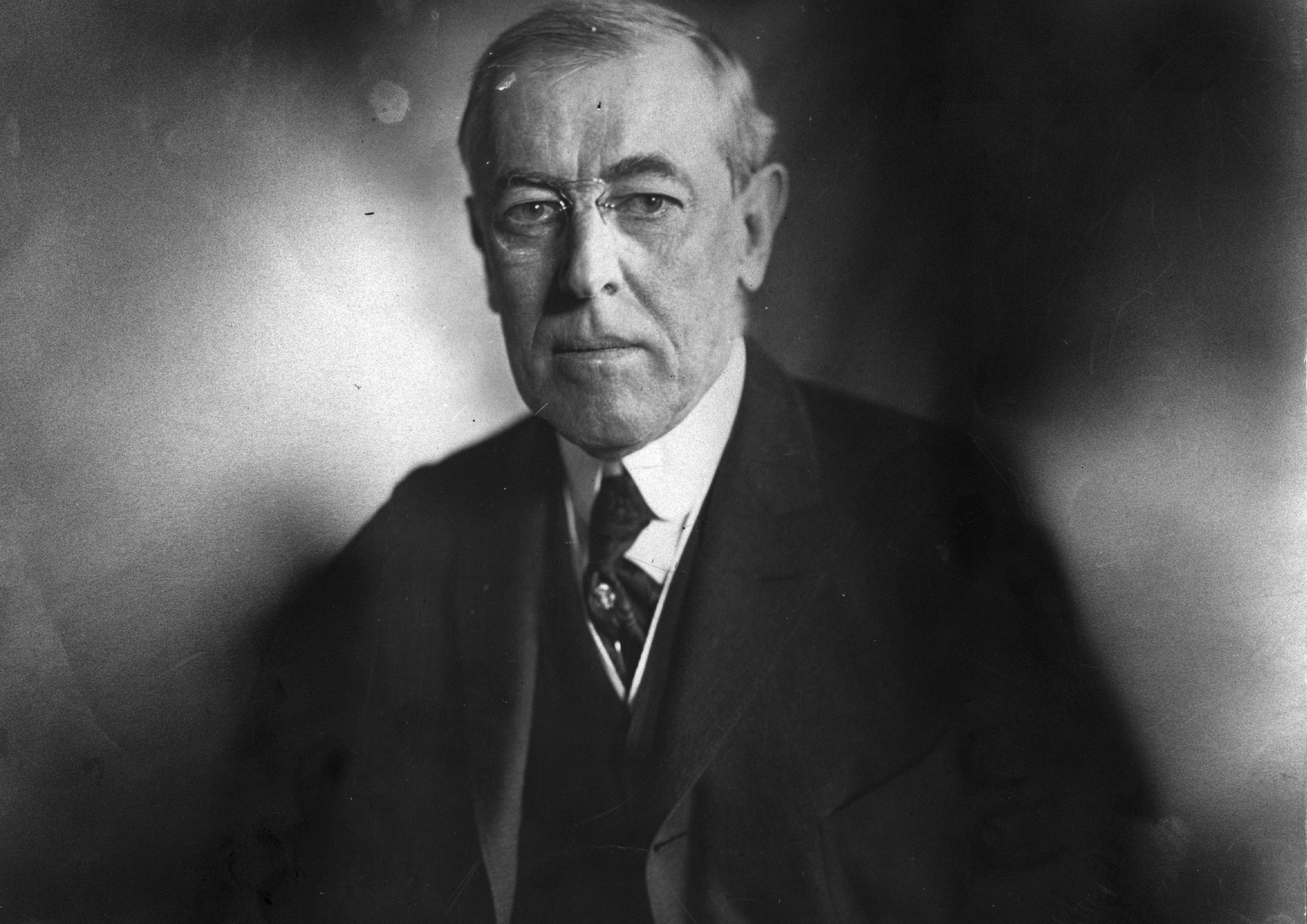

A family deported back to Central America in 2014.

This doesn’t violate the legal principle against sending someone back to danger — as long as, as Vanessa Allyn of the advocacy group Human Rights First points out, there’s a “case-by-case assessment.”

And the federal government has maintained, since starting the raids and deportations at the beginning of 2016, that it is only targeting families who have, as the senior administration official put it, “exhausted appropriate legal remedies.”

But if the US is sending some people back to El Salvador or Honduras, while recognizing that other people are in too much danger to return, it had better be damn sure that it’s getting it right.

How sure is the government that it’s not sending people back to their deaths?

The advocates are worried that the US’s desire to deter people from making “the dangerous journey” is making it less likely to give a full and fair assessment to people who seek asylum here. “They’re finally recognizing in the region that Central Americans in fact are refugees,” Young says, “and yet we’re still treating them as undocumented, unlawful arrivals when they arrive at the US border.”

Yet Honduras has one of the highest murder rates in the world of any country that isn’t at war. So it could be likely that those going back face a grim demise.

It’s not like the US has a great track record with asylum seekers in the recent past. One man deported to Honduras in 2014 told Human Rights Watch that “I asked for asylum, the officer told me don’t apply.” He and the other deportees interviewed in the report said they were in grave danger in their home countries — afraid to see their kids or even tell their families they were back. And some deportees have, in fact, been killed after their return.

“The people fleeing who make it to the US are really the exact same people that we’ll be processing in the region,” says Young.

Human Rights Watch The scars of a Honduran man injured in a gang attack. The US deported him back to Honduras in 2014.

Young is worried about a revival of the Haitian crisis of the early 1990s. The US government opened up “in-country” refugee processing for Haitians, but used it as an excuse to start interdicting boats of Haitians trying to flee to the US. “They were really trying to circumvent Haitians’ arrival in the US, and keep them offshore and manage it that way,” she says.

The administration doesn’t put it that way. But it does acknowledge that its strategy is, in part, to deter people from using smugglers to get to the US while the government works to provide the “safe and legal alternative.” “We cannot encourage folks to take that dangerous journey,” said the senior administration official.

The courts and Central American countries are worried the US is moving too fast

Advocates complain that asylum cases are being heard on a “rocket docket” that doesn’t give immigrants a fair hearing in court. And it seems that the nation’s highest immigration court shares their concerns — and doesn’t agree with the administration that the people it’s trying to deport have “exhausted all their options.”

Soon after the first round of raids, lawyers asked the Board of Immigration Appeals to issue emergency rulings to halt the deportations of six of the Central American families. Within hours, the board granted those rulings in five cases.

Advocates were stunned. “The board never acts so fast,” Wendy Feliz of the American Immigration Council told the Houston Chronicle. “This is totally unusual.”

And the stays kept coming. More than 20 of the first 121 immigrants arrested in the January raids have gotten stays — almost all of those who had lawyers fighting their cases.

The reasoning for the stays isn’t provided. But advocates and Hill Democrats have taken the court rulings as evidence that judges share their concerns — that the government hasn’t proved it will be safe for these people to return, after all. “The fact that several of these families were subsequently granted emergency stays of removal indicates that the system has failed these refugees,” wrote 142 House Democrats in a sign-on letter to the administration. “We are gravely concerned that DHS may have already removed mothers and children from the United States and returned them to violent and dangerous situations in their home countries.”

In an even more extraordinary development, the government of El Salvador stepped in to stop 22 people from getting deported back to its country. In 2014, Central American governments cooperated with deportations and endorsed the US’s strategy; this time, a Salvadoran official told the press, “No compatriot detained in the raids will be deported until all legal measures have been exhausted.” Three Salvadoran families were literally pulled off the plane that was supposed to take them back.

This certainly doesn’t indicate confidence in the Obama administration’s claims that it’s only deporting people after ensuring they won’t be in danger.

According to the senior administration official, applying for refugee status in Central America is the “vastly preferred alternative” to coming to the US and requesting asylum. But as Young points out, they’re the “exact same people.” The administration is struggling to balance the humanitarian need to make the right decisions against the deterrent need to deport people quickly and efficiently.

The stakes are literally life and death.

via : Vox – Policy & Politics